Past

TRUE RELIGION

21 Dec - 24 Feb, 2024. Arles

Exhibition details:

TRUE RELIGION

21.12.2023 – 24.02.2024

Curated by Pentti Monkkonen

Artists:

Liz Craft

Keith Farquhar

Nikolas Gambaroff

Richard Hawkins

Benjamin Lallier

Malene List Thomsen

Sara Mackillop

Stephen Suckale

Stewart Uoo

Gallery:

19, rue de la Madeleine

13200 Arles

This building was originally a church, then later used as a stable, and now an art gallery. My idea was to hang an exhibition that made the space back into a church, at least in terms of the works I choose and their placement. It’s a bit like an actor who was once really in a gang playing a gang member in a film. This was once a church and now it plays one in this art exhibit.

Art used to have a more defined relationship with architecture, especially in a place like a church; multiple artworks were installed permanently over long periods of time. Contemporary exhibition spaces usually host an ever-changing series of different shows put up and taken down, much like a theater. The curator of a group show is a bit like the theatrical director assembling a troupe of artworks to perform in some semblance of cohesion to a unifying theme or connection; of course, each artwork stands on its own, each artist usually made the work for a different context.

– Pentti Monkkonen

Here are the statements of the artists in the show about their work:

Liz Craft

For Alexey Pajitnov, the inventor of Tetris, “games allow people to get to know each other better and act as revealers of things you might not normally notice, such as their way of thinking”.

Liz Craft (b. 1970, Los Angeles) is a Los Angeles installation artist and sculptor. She used to co-run the Paradise Garage in Venice Beach, California. Her artwork has been exhibited internationally and collected by museums including the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, LACMA, and the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles. She currently lives and works in Berlin, Germany.

Keith Farquhar

I began working with clothes in the first year of the new millennium. My best friend Craig Gibson, hailing from a working-class background like myself, had gotten himself a job in shop, a family-run business specializing in climbing and outdoor gear in Edinburgh. Craig, being bright (some might say too bright for his own good) caught the manager’s attention, and eager to maximize his potential, trained as one of the firm’s window dressers alongside his more mundane tasks. Craig’s tuition was conducted in-house, under the wise guidance of a middle-aged heterosexual man. We are talking here

of the unglamourous end of the window dressing spectrum, certainly not the echelons of Johns, Rauschenberg and Warhol. Yet, Craig’s resulting windows, although somewhat naïve and certainly not sophisticated, were striking in their own right, and witnessing these served as my own introduction to creating artworks with clothing.

My mother was, and still is an adept seamstress: whether it be clothes, curtains or cushion covers, and around this time I enlisted her to craft several artworks for me. A John Lewis logo-meets-Blinky Palermo fabric painting, carefully stitched from my instructions, now hangs in Le petit Royal restaurant in Berlin. Another; a giant snake draught-excluder, featuring a life-size human figure silhouetted along its profile as if a recent meal in mid-digestion also remains a standout. Collaborative works such as these with my mother can I think be aptly described as folk art: A family effort imbued with the imperfections of the self-taught, amateur in the best possible sense. In addition to utilizing her skills as a seamstress, working with my mum was a way of sharing my newfound creative opportunities with her. I was seriously ill as a child and she had had too many responsibilities looking after me as well as her own mother to flourish creatively herself in what was a patriarchal, class-bound culture. Collaborating was a way to keep her in the loop of what her newly, socially mobile son was finding out and dreaming up.

My first clothes works emerged thus, from the creative labour of my mother and my best friend. They were improvised with what was available at the time: items in drawers that could be repurposed: “How interesting is a boring jumper compared to it becoming a figure in an exciting artwork?” mused my adolescent mindset as dressmaking-scissors and a staple gun became my tools of choice. Over time, I honed my methods to an absolute economy of means. I could cut a profile from the back of a jumper or

shirt and fold it up through the collar to create face, head, neck and torso all interconnected. This would be staple-gunned to a backboard or later, in my ongoing thirst for greater efficiency, directly to the wall, although the latter I soon found out was detrimental to sales. Who knew that collectors wouldn’t invest in works that couldn’t be moved? Duh! Perhaps the pinnacle of this phase took place at Basel Unlimited in 2004 where Craig and I co-orchestrated a 20-meter-long temporary frieze entitled V necks versus Round-necks, featuring a legion of Scottish lambswool jumpers and jeans. Charles Saatchi bought it and it’s never seen the light of day since.

Around this time my first hoodie works appeared. Beyond the hoodie symbolizing the antagonistic side of youth culture (believe me, this is something I wanted to give the artworld in spades) I was thinking on a formal, anatomical level: As I wasn’t into using mannequins, wanting to make figures solely with clothes, and jumpers and shirts don’t have heads, how could I create a head for the garment without being too literal? The hoodie’s hood provided the solution, allowing me to craft a draped torso complete with head without requiring any cutting. Hanging became simpler too; these new figures could be affixed with a single, deftly placed staple through the crown of the hood, and this, in turn, moved the work into a more conceptual realm, allowing for the possibility that a third party could install them according to my instructions. Over the years, they have been installed by various institutions and galleries, always with me okaying the final hang via video or, latterly, Skype. Now, more than two decades on from their initial inception, Pentti has found a new context for the hoodies. What were rebellious youths are here reimagined as makeshift monks in an exhibition at High

Art’s Chapel Space in Arles. It’s easy to observe the duality implicit in the hooded forms: Street-corner louts that are also figures deep in contemplation and it’s amusing for me to further imagine that the hooded youths have now grown up. Is it conceivable that their antagonism has been channelled into something less destructive, less oppositional, with the passing of time and perhaps the aid of some much-needed therapy?

Keith Farquhar’s (b.1969, Edinburgh) recent solo exhibitions include : Neuer Essener Kunstvarein, Essen, Germany; Cabinet, London, England; Leslie Fritz Gallery, New York, USA; New Jerseyy, Basel, Switzerland; Hotel, London, England; Focal Point Gallery, Southend, England. Group exhibitions include : The Hole, New York, USA; Cabaret Voltaire, Zurich, Switzerland; The Box, Los Angeles, USA; Gregor Staiger, Zurich, Switzerland; Witte de With, Rotterdam, Netherlands; Kunsthalle Freiburg, Switzerland; CAPC, musée d’art contemporain, Bordeaux, France; Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh, Scotland; Gio Marconi, Milan, Italy; Badischer Kunstverein, Karlsruhe, Germany; Gagosian Gallery, New York, USA; Kunstverein Braunschweig, Germany; David Zwirner Gallery, New York, USA.

Nikolas Gambaroff

Everything here began with a question of faith. I started doing these readings a few years ago—mostly for friends, soon for a wider group interested in the mirror of their social realms—perhaps their personal or professional power struggles. The formats evolved, took place in varied environments. They aided some in grappling with their tangled pasts or present social, familial knots. Some were bothered, others found solace; many left with a sense of unease. Perhaps it was a way to forge connections anew. Or to better understand the social fabric I had, in recent years, mostly severed. The more I think about our present moment, the more faith re-emerges—a recurring motif. It morphs, crystallizes when existential desires and dreads rise to the surface, when the social fabrics people are woven into fray, become fraught or tenuous. I’m not dismissing faith; rather, I want to believe, I’ve dreamed of it many times. Taken in by an ineffable presence, cloaked in truth. Finally belonging deeply,

dissolving into belief.

When I grew up in Germany in the 80s and 90s belief was structured differently, it still had a distinct taste and feel. We mostly rejected it, fundamentally, at least that was the appearance. Again, don’t get me wrong, belief was what I sought—anything to hold onto really. We tried! We drifted among scenes, subcultures, identities. Sampling at will—touching down, then off again, like drifters skirting the edges of all that was en vogue, of every stratum of society. Now, I merely grasp at the fleeting shades of personae I see, as they shift and harden into new silhouettes, new constructs. I recall when the notion of money as we know it today first struck me. The Cold War was a constant, immutable, its factions clearly defined, Germany still bisected. My life and outlook were very different at the time. The world seemed different; one wasn’t touched by the streams of digital information as much back then. Money’s role was tangible, human connections palpable, the world itself a solid thing, and so too our beliefs seemed to be real. It was already make-believe as well obviously, but it appeared to be real.

A well-crafted make-believe, with a veneer so convincing it might as well have been authentic. The veneer itself traded like currency. Not that everything changed since then, we’re still in the same game, just that now the rules seem superfluous at best. They are merely there to blind you, maybe to offer the illusion of solid footing. I looked over to my friend whose family constellation I was disentangling, she asked me: ‘Do you actually believe in this?’ My gaze settled on the game board, on the pieces that lay there as if in judgment. ‘Unfortunately… I do’; I confessed.

Nikolas Gambaroff (b.1979, Germany) currently lives and works in Berlin and Los Angeles. In his artistic practice he deals with linguistic shifts in meaning and the associated ambiguities in art. His work is anchored in painting, which Gambaroff expands to include sculpture, installation and performance depending on the content of his projects. Recent solo exhibitions have taken place at The Kitchen, New York; Meyer Kainer, Vienna; and Overduin & Co., Los Angeles. His works have also been shown in New York at the Museum of Modern Art, the Whitney Museum of American Art and the ICA in London.

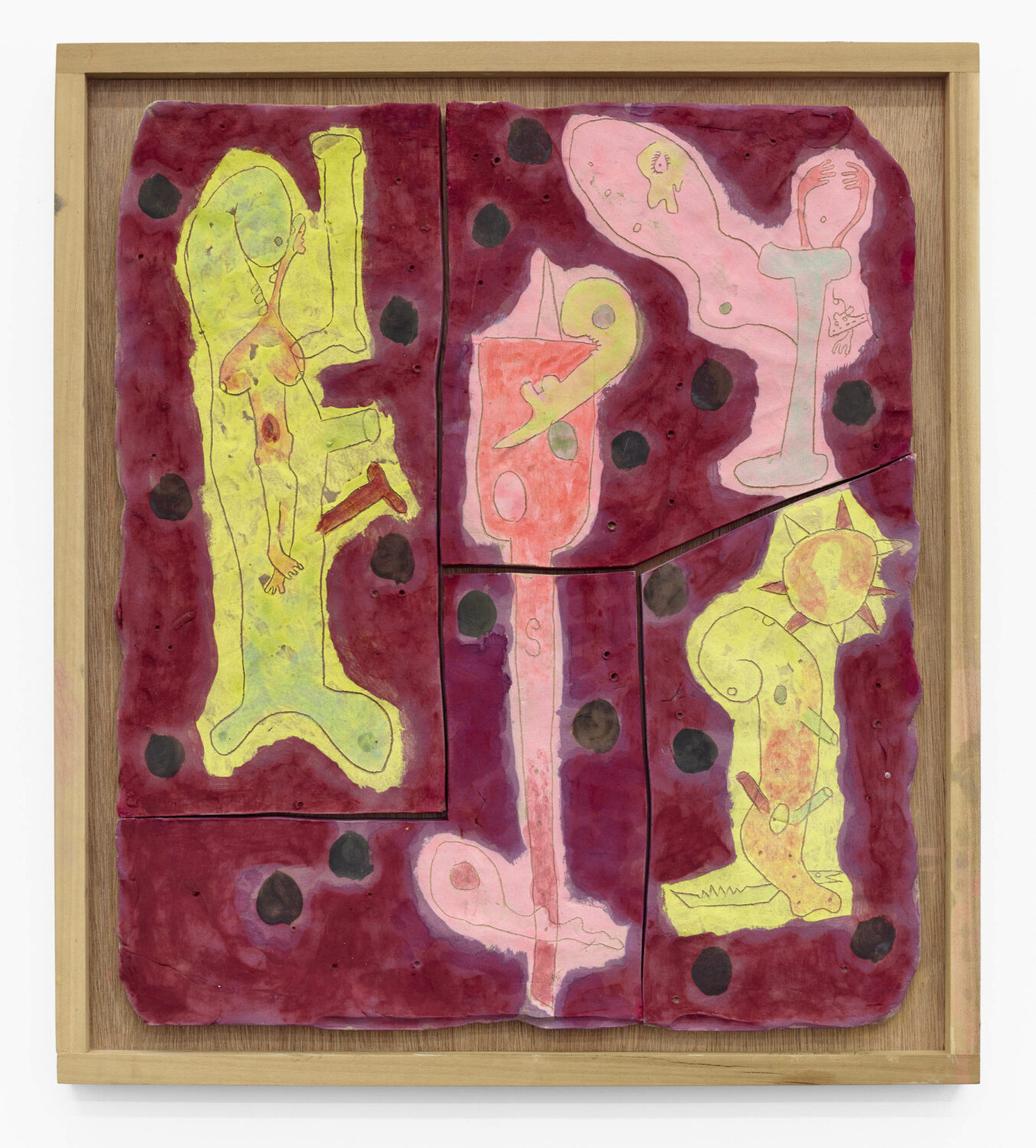

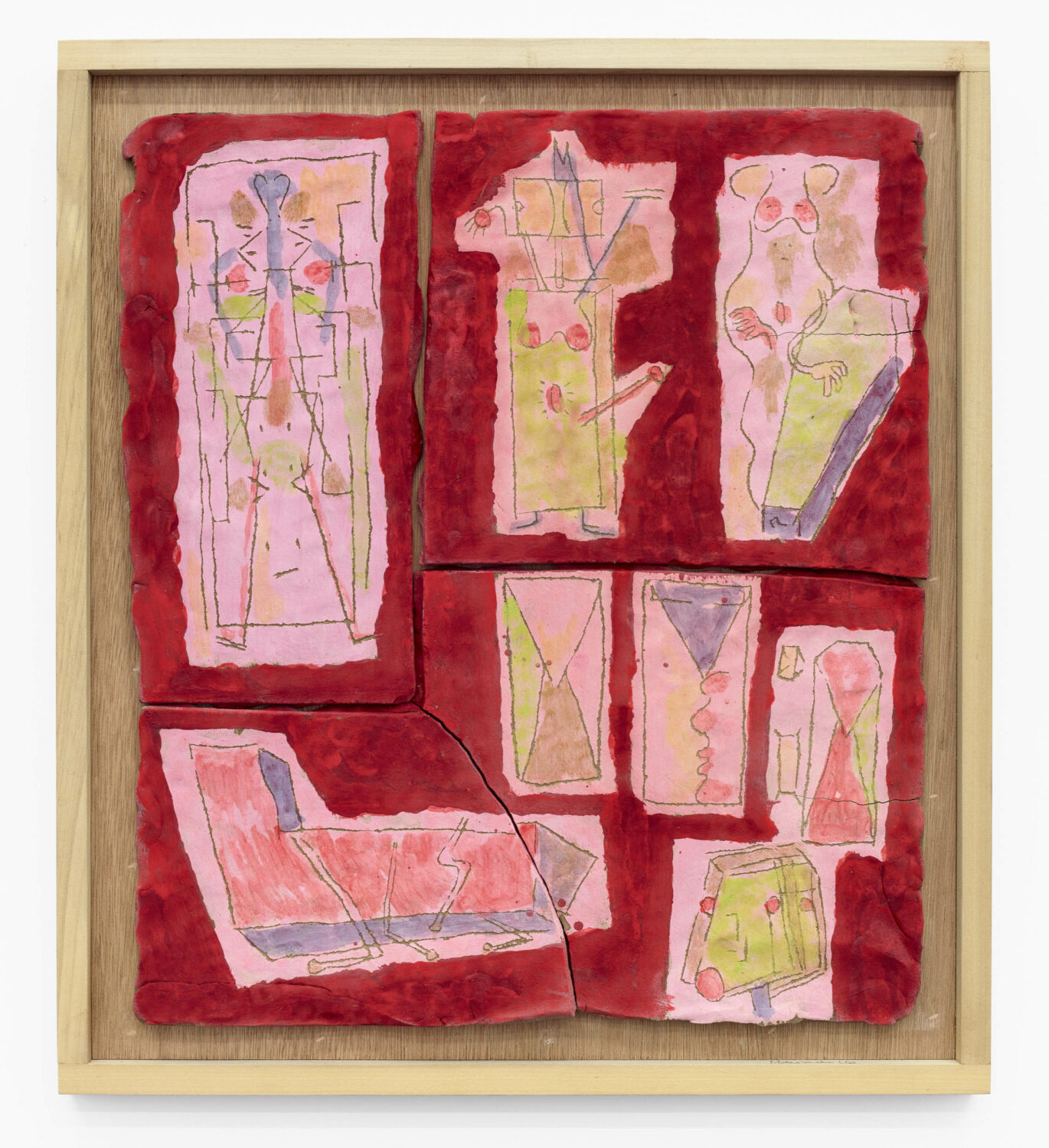

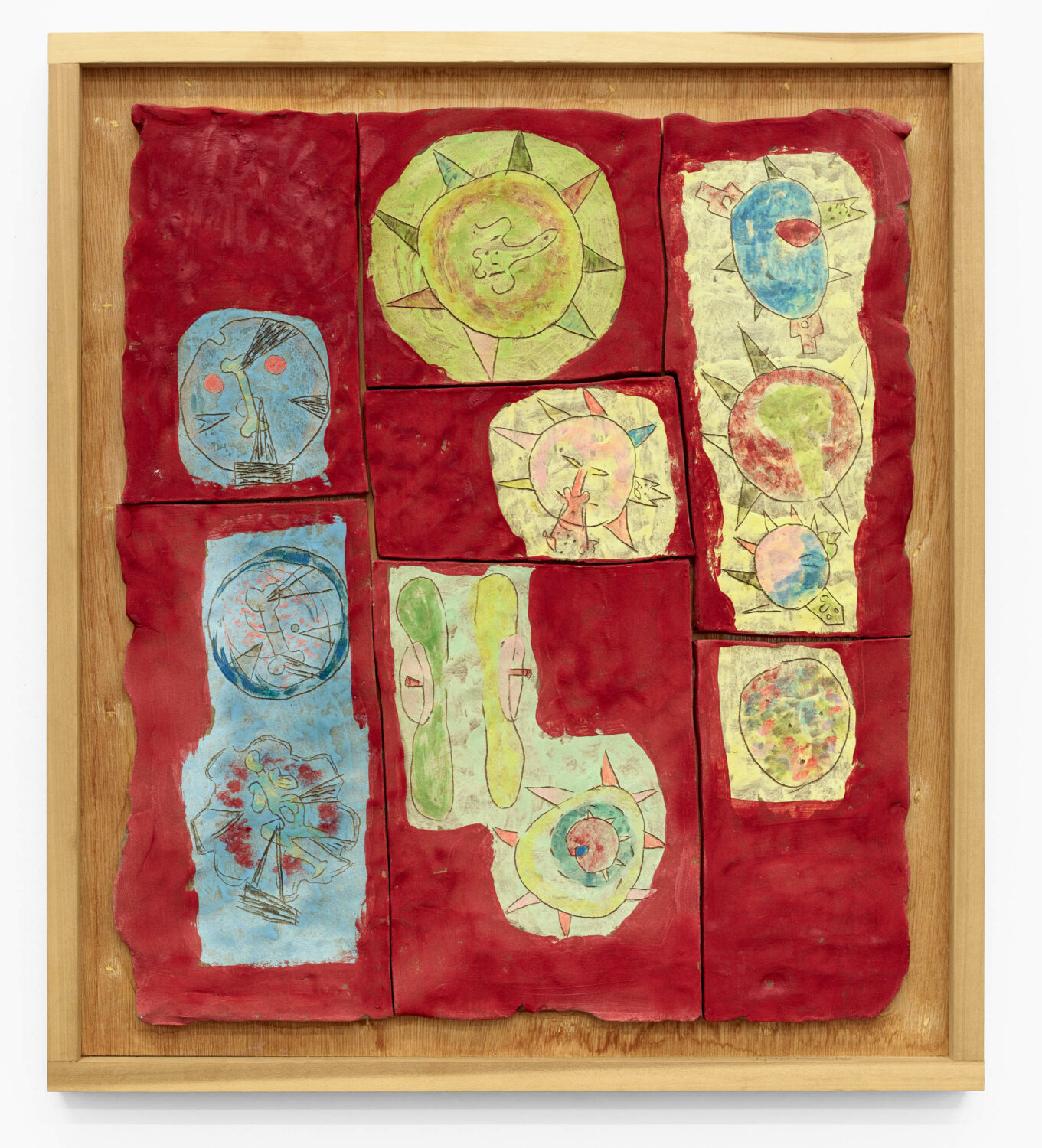

Richard Hawkins

One instance – and for me a very productive one – was taking “Le Minotaure” and removing the central dominating figure as well as the more overt of the figurative elements. What are left, as can be seen in my two ceramics “Paper Crypts”, are the following elements: a diagram-like pseudo-figure that makes one think of anatomical and acupressure charts as much as torture racks, operating tables and patients strapped down and submitted to ECT charges; two paired almost-cubist figures, one with

breasts and rising from a coffin, the other more abstracted and somewhere between a storage cabinet and a robot, a coffin in the shape of an odalisque a la Magritte (though Magritte’s earliest works in this vein date from four years later) but with linear paths buzzing – like flies – from its interior and, lastly, what seems to be a mechanomorphic face — flat, blank and transparent. Five other elements bear much less of a relationship to the human figure and take the form, instead, of sealed envelopes and folding tables with legs closed, extending and fully extended. The final element, almost minor in comparison to the more identifiable and usually larger elements, is a quiet little drawing, no more than ten pencil lines and stained with rubbed-in blue and brown crayon and indicates a shape that is both envelope and coffin. By cracking off elements from the rest of the drawings and focusing on this very small seemingly minor one, a new connection within Artaud’s iconography occurs from all the way back to his writings on the Black Plague through the gris-gris spells and all the way up to his use of coffins in drawings from January through March 1946. If one imagines that the spells were meant to carry within them a shock upon first sight, and it is only the reading of them by the recipient that allows the spell or curse to take full effect, then the envelope that contains them should preferably not reveal too much of their contents. Combine this with the convention of coffins not only housing corpses but also suppressing contagion and you have an interesting correspondence: the envelope is to the curse what the coffin is to the plague-ridden corpse.

Richard Hawkins (b. 1961, Mexia, Texas) is an American artist. He lives and works in Los Angeles where he serves as Professor of Painting & Drawing at the University of California, Los Angeles. His works are held by museums including the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Museum of Modern Art, and the Art Institute of Chicago

Benjamin Lallier

The painting is a sun-bleached velvet blown-up version of a GG Allin picture I bought from his brother Merle. It was part of the family album until their mom died a few years ago. Their dad Merle took the picture in September 1956 (the month my mom was born). The two sculptures are benches I bought from a church in Berlin for my show The Cat Loves The Mouse, The Mouse Hates The Cat. One of the two pews was vandalized during the show by a visitor who engraved the word “SHIT” on it. That event influenced the title of that piece to become SHIT when it was previously The Logic of Superstition.

Benjamin Lallier (b. 1985, Marseille) is a multidisciplinary artist based in Berlin. Lallier has a nonexclusive relationship to a number of media. His work ranges from sculpture, painting and drawing to installation, often ignoring the traditional formal constraints each medium seemingly imposes. His work explores a broad spectrum of interests, ranging from scientific theories to the prosaic aspect of some pop culture markers. The artist is also largely influenced by the punk culture and ideology of DIY aesthetics, anti-conformity, anti-consumerism, and satire. His work explores the

humor, poetics, and manipulations of everyday situations and popularly held beliefs. Lallier calls attention to the nuances within a world of often unchallenged stereotypes. Certain moments are simultaneously playful, and deeply somber. The artist’s willingness to dwell in interstitial, apparently contradictory emotional registers endow the works with a peculiar and often surprising humanity; conflicting feelings don’t just sit atop one another, but share the same space, as they do in life.

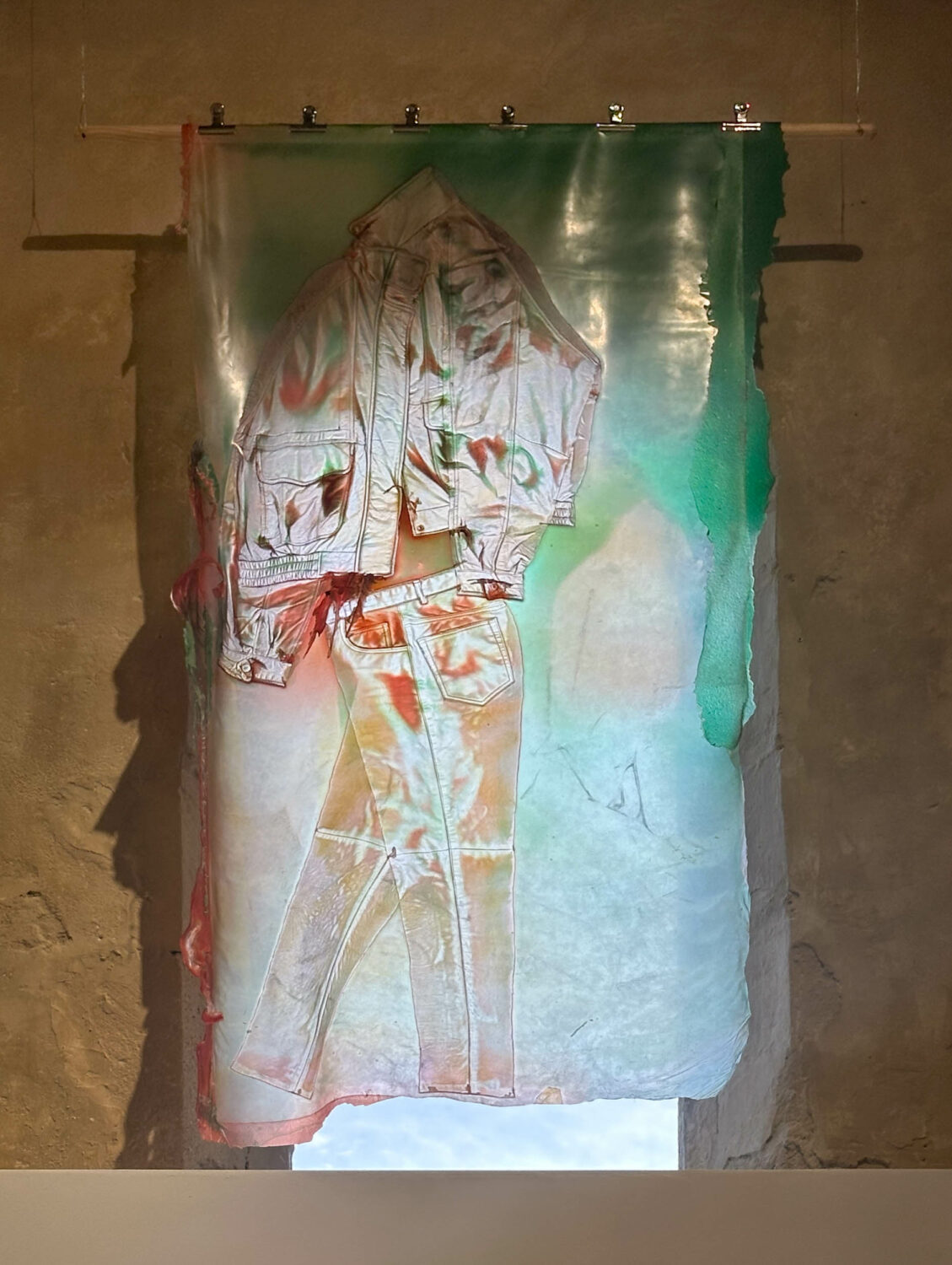

Malene List Thomsen

After many years in fashion, I, a while ago, turned away from that field. The three works are remnants of that time, Wiedergänger in their own way. Two are large, and one is small, like this chapel’s windows. I like to think of the small one as ‘bébé’. They are subjects without a body, giving testimony to their own brutal past, first as cows’ skins, then as mass-market garments. Now, cast in latex, they fan out our sun’s divine light into many colours, before that same light turns them to dust once and for all.

Malene List Thomsen (b. studied Women’s Wear at the Royal Academy, Copenhagen and Central St. Martins, London. She has previously exhibited at Kunstbunker Nürnberg, Galerie der Stadt Schwaz, and Ve.Sch, Vienna, as well as Lars Friedrich, Berlin and David Lewis, New York, amongst others. She lives and works in Berlin, Germany.

Sara Mackillop

A selection of publications made between 2010- 2023 are displayed. The publications have in common an attraction to the details of printed retail and bureaucratic detritus and an engagement with the many forms of a publication, its pages, bindings and sequences. The uninvited remakes of IKEA brochures are self published and digitally printed made every year from 2015 to 2018, each uses the original found brochure as source material reimagining their design, removing and overlaying

content and product information, repeating lines and shapes to interfere with rather than elevate the original. IKEA Tottenham 2023 is a more traditional photo publication of images of the shop the weekend before it closed down. In Catalogue, Envelopes Midwinter and Laptop a genre of publication rather than a brand is considered, similarly One Day Diary reorganises a traditional diary, heightening and concentrating time use by spatial organisation. The selection is made according to availability and

the curator has arranged the display. Sara MacKillop (b.1973 in Bromley) reappropriates objects linked to the stationery store, as the tool itself of artistic production or an element of mass distribution. Paper, file boxes, mail-order catalogues, pens, books, vinyl sleeves, envelopes are subtly transformed by the artist into volumes that humorously evoke minimal forms. Methodically fascinated by these daily objects and their perishable nature, Sara MacKillop cuts them out, copies them and arranges them in space revealing their fragility while giving them a sculpture dimension. MacKillop lives and works in London.

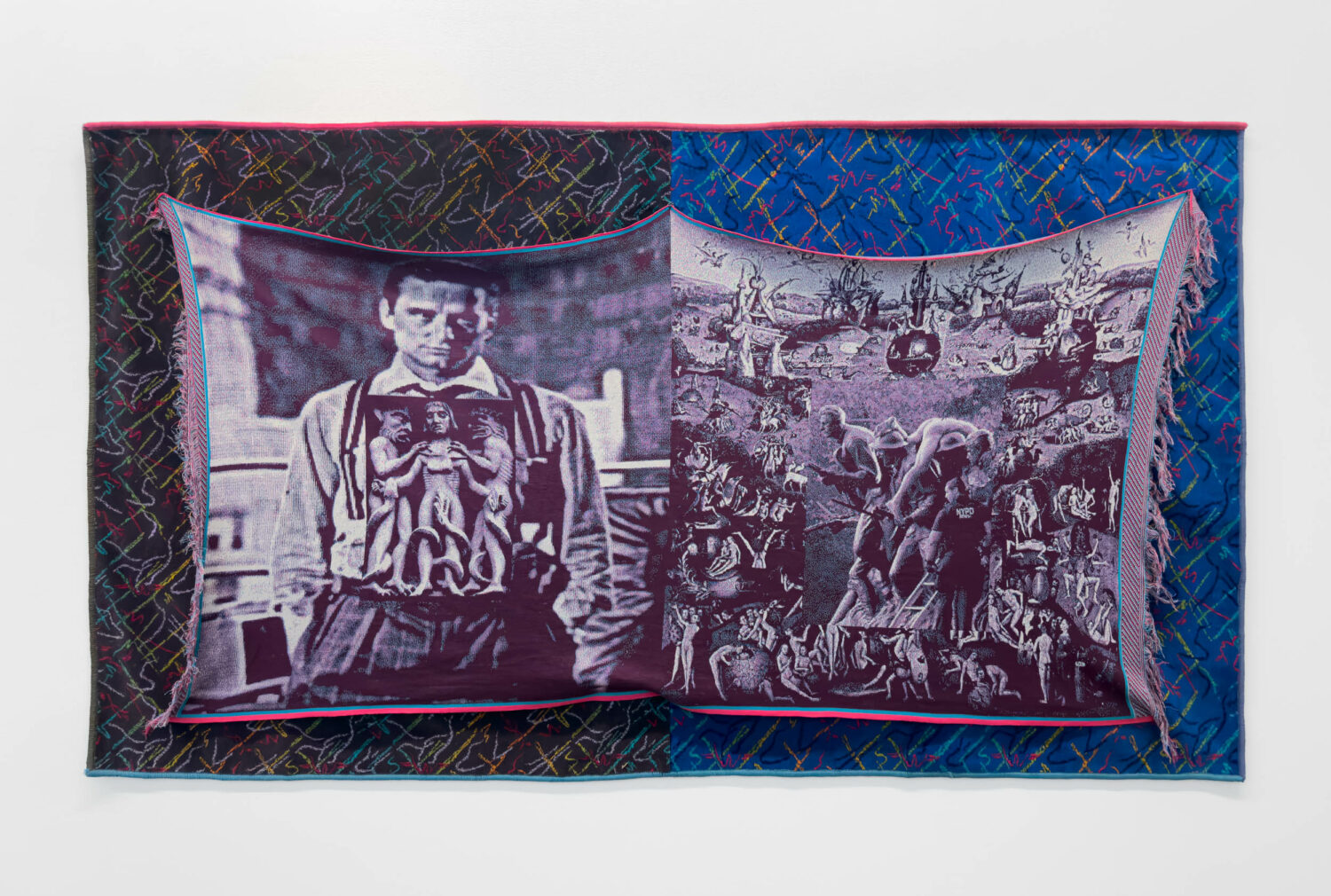

Stephen Suckale

Stephen Suckale’s series “Picture Memory” features a selection of tapestries made from jacquard fabrics mounted on woven seat cover textiles from public transportation. The latter are known for their durability, distinctive patterns, and use as anti-vandal fabrics in commuter and subway trains.

The works on display address various aspects of a loss of control that is connoted as sinful. Human states such as desire, gluttony, greed, sloth, anger, envy, and pride form a basis of capitalist structures and production mechanisms.

Joseph-Marie Jacquard, a renowned 19th-century master weaver, developed the Jacquard loom process that enabled the automated creation of complex patterns and designs through the use of punch card control. This groundbreaking innovation revolutionized the textile industry and laid the foundation for the automation of weaving processes.

In Stephen Suckale’s pieces, this important historical heritage is linked with current social and technological developments and those human tendencies that make permanent economic growth and ever faster production processes necessary in the first place. This creates an exciting dialogue between traditional craftsmanship and the design possibilities of machine learning. Thus, the work seems to bite itself in the tail on a formal and content-related level – like the allegory of the selfconsuming snake.

Stephen Suckale (b.1979, Frankfurt am Main) is a contemporary artist, museums such as Philipp Pflug Contemporary have featured Stephen Suckale’s work in the past.

Stewart Uoo

Don’t Touch Me (Fresh and Local Eggs) is roughly based on the idea of the modern consumer leisurely at the grocery store or farmers market.

Stewart Uoo’s (b. 1985, California) practice explores where the social and digital overlap often incorporating fashion and video game aesthetics into his watercolors, sculptures, and video pieces. Recent exhibitions include the 9th Berlin Biennale and the 10th Gwangju Biennale and were featured alongside artist Jana Euler in a two-person exhibition at The Whitney Museum of American Art in 2013. Uoo has exhibited at 47 Canal in New York, Galerie Buchholz in Berlin, Germany, and Mendes Wood in São Paulo, Brazil, amongst other galleries. Uoo is the host of It’s Gets Better, an art performance event held every summer that showcases artists, musicians, poets, and fashion icons. Uoo lives and works in New York, USA.