Past

Orion Martin

Tête

04 Apr - 25 May, 2019. Paris

Exhibition details:

Orion Martin

Tête

Apr 4 – May 25, 2019

Gallery:

1, rue Fromentin

75009 Paris

Image:

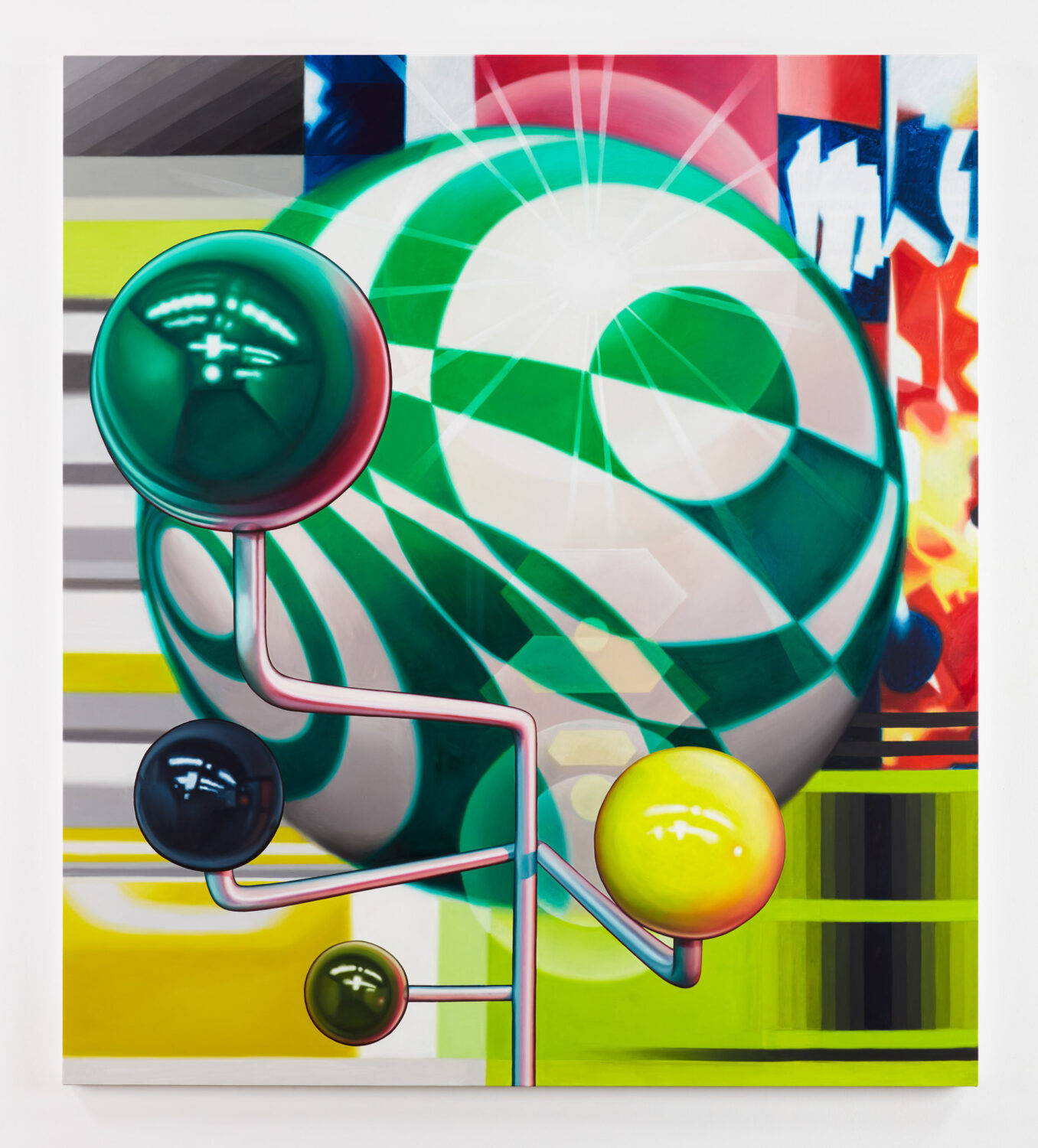

Assembly, 2019

Oil on canvas

182.9 x 162.6 cm / 72 x 64 in

It’s called what it’s called because of the anecdotal, apparently common misconception that Nelson Mandela died in prison in the ’80’s, when in fact he was released from prison 30 years before his death in 2013; other examples include the fact that people frequently misremember the children’s picture book series “The Berenstain Bears” as “The Berenstein Bears,” and sometimes people think that the United States has 52 states (that the continental US was 50 before Alaska and Hawaii’s additions). Theorists of the Mandela Effect like to explain the phenomenon through quantum physics, string theory, and the concept of alternate realities: for them, a common conflagration about history, or spelling, or geography, is a collective psychic recall of an alternate reality where that perspective is fact. This line of thinking has gotten more play online in the past few years, as certain world events have cast so much disbelief over everything that people are grasping at straws to make sense of a world that they didn’t think was possible, even entertaining the idea that we’ve fallen off the “correct” timeline. Denial, of course, is the first stage of grief: the Mandela Effect is just one sci-fi expression of our broken collective brain, our head buried in the sand.

It’s in that burrow that attempts of rationalization are made. Unbeholden to any outside rules, the mind takes what has been given and contorts it, half cognitive and half libidinal. Sometimes, huge associative leaps are made, and then they are made to seem perfectly natural. The result is often unrecognizable from its starting point, or insular from the world that produced it. Misunderstandings of Nelson Mandela’s history can be easily explained without resorting to string theory, but for whatever reason it’s string theory that helps us feel like we still have a grasp on things – or, at least, that having a grasp is still possible.

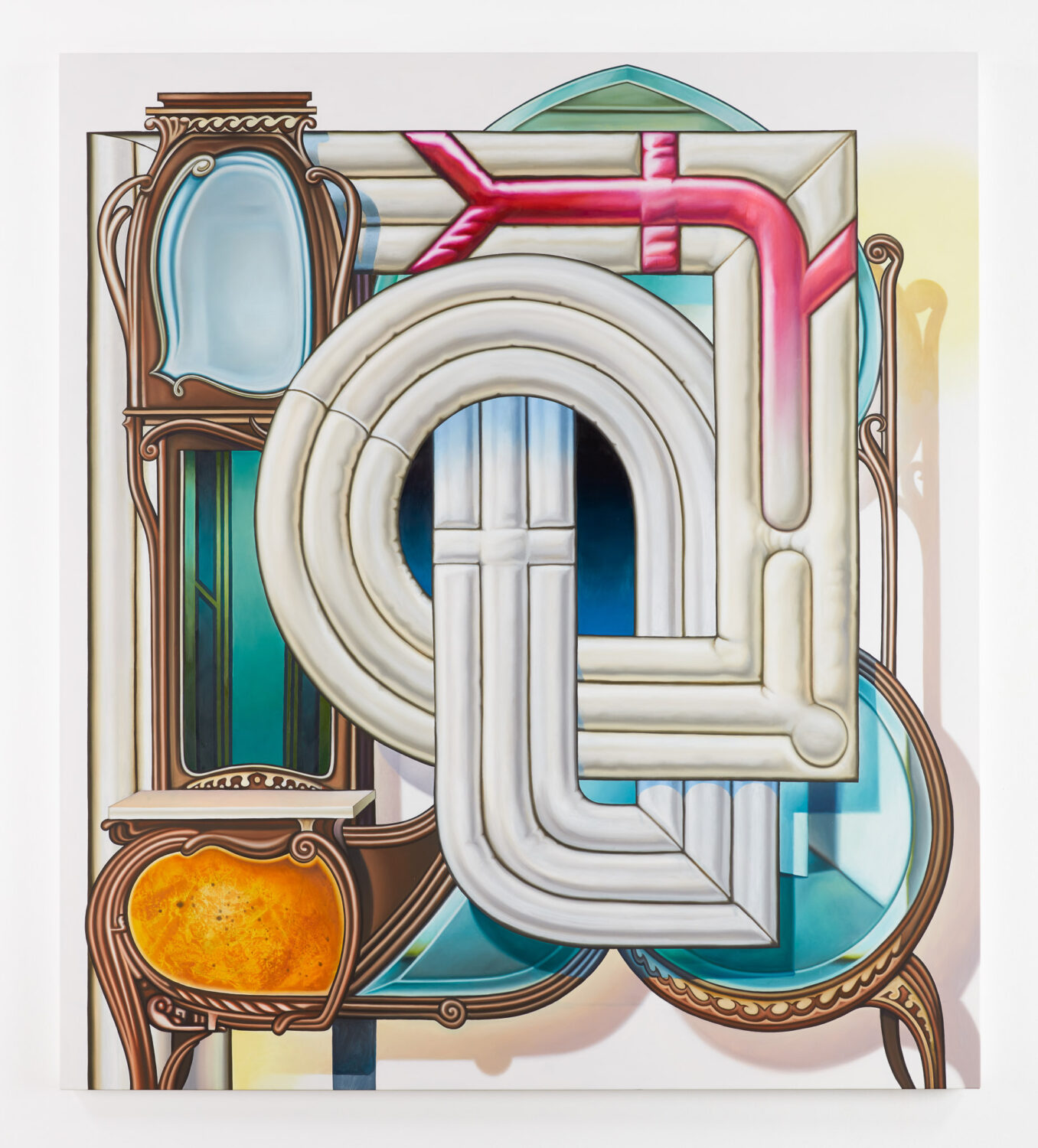

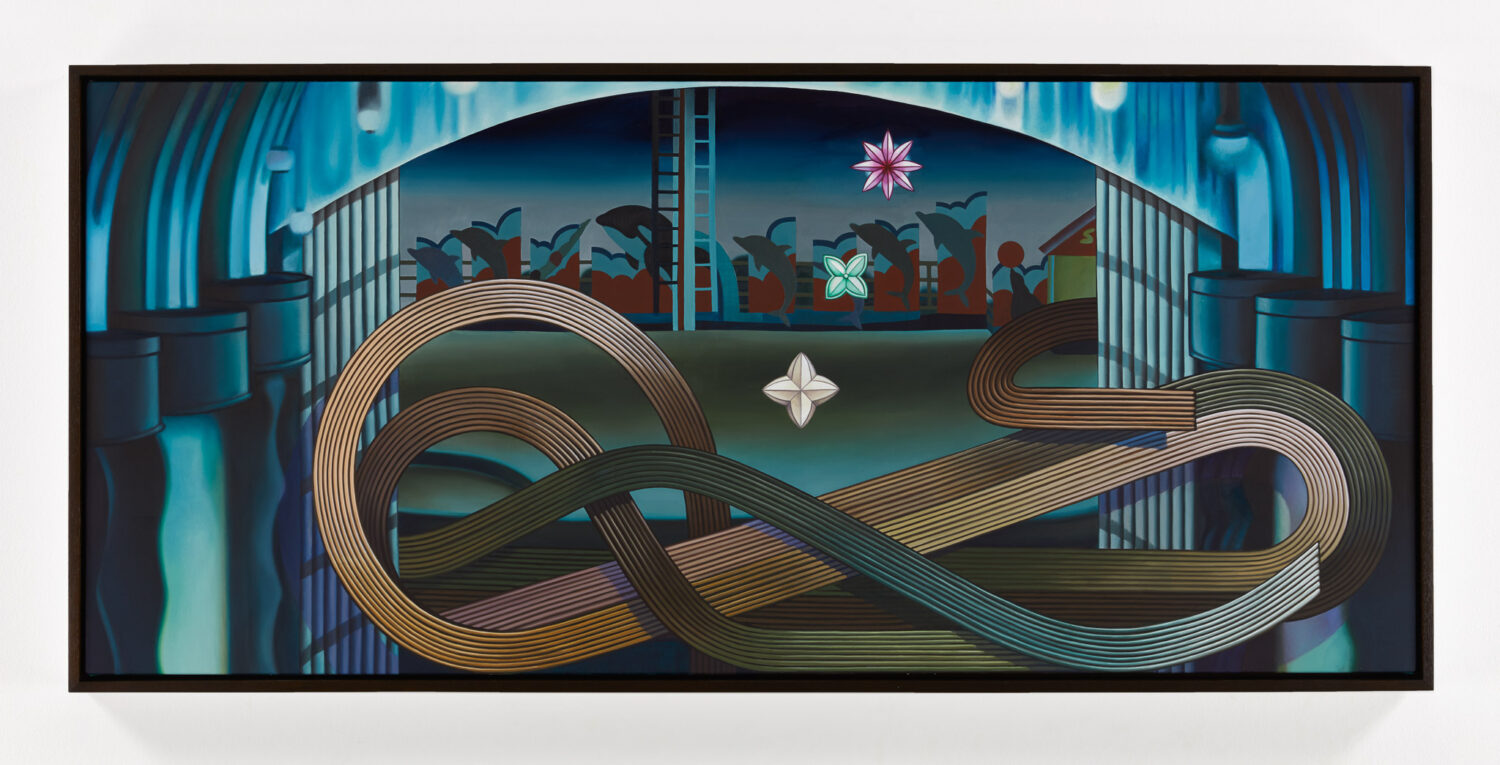

When you look at Orion Martin’s paintings, a similar process of contortion is sometimes applied to familiar objects. In “Hangar,” a basketball sneaker is dissected and augmented into something else entirely, through a process that’s partly like mapping and partly like poetry. The paintings have a way of taking ideation past the point of capture, and bringing objects to a extradimensional, otherworldly place – a thing can look so perfect, yet somehow so ‘wrong’. But like the baroque lattices of a conspiracy theory’s diagram, a thing can be both unbelievable *and* true. The fulcrum of fakeness and realness is a familiar axis in Orion’s work, but the works in this show bring with them a particular air of dread. There’s a preponderance of gray gauzes and cold, clinical technologies, some tobaccostained in places. In “With Gas,” pointy flower-sirens sound off before a burning house; in “Assembly,” an Eames coatrack puts its fists up at us; in “Homeopathic Remedies,” zits erupt from a porcelain face, and a medical patch fails to obscure them. In ways big and small, there’s a brooding feeling that something is wrong, just below the surface, making its way up and out.

The “Tête” sculptures carry their anxiety in other ways. When wrapped in leather, they are laced tight, and the leather is sutured to fit their form perfectly; when exposed, their glossy surfaces are blemished with inlaid scraps of wood and paired with tarnished antique mirrors. Since they are heads without faces, it’s unclear which part ‘faces’ the mirrors, and therefore which parts get distorted at their reflections’ edges: they are heads without orientation, either narcissists or avoidants, doubled in our inverted world.

– Nick Irvin