Past

Lucy Bull

Sisper

19 Dec - 20 Feb, 2021. Arles

Exhibition details

Lucy Bull

Sisper

Dec 19, 2020 – Feb 20, 2021

Gallery

19, rue de la Madeleine

13200, Arles

Metaphysical horror master H.P. Lovecraft begins his 1928 short story “The Call of Cthulhu” with a bleak observation. “The most merciful thing in the world, I think, is the inability of the human mind to correlate all its contents,” the story’s narrator muses. Getting blacker still, he continues: “We live on a placid island of ignorance in the midst of black seas of infinity and it was not meant that we should voyage far. The sciences, each straining in its own direction, have hitherto harmed us little; but some day the piecing together of disassociated knowledge will open up such terrifying vistas of reality, and of our frightful position therein, that we shall either go mad from the revelation or flee from the deadly light into the peace and safety of a new dark age.”

Like all good horror does, the passage proposes a promiscuous intermingling of the interior and the exterior worlds, a blending of our terror of the monsters that lurk just outside the klieg lights of established science with the fear of the specters that haunt the penumbral corners of our unconscious minds. Look close enough, Lovecraft suggests, and disentangling these seemingly opposing poles might be an impossibility. It is a territory not fit for the faint of heart.

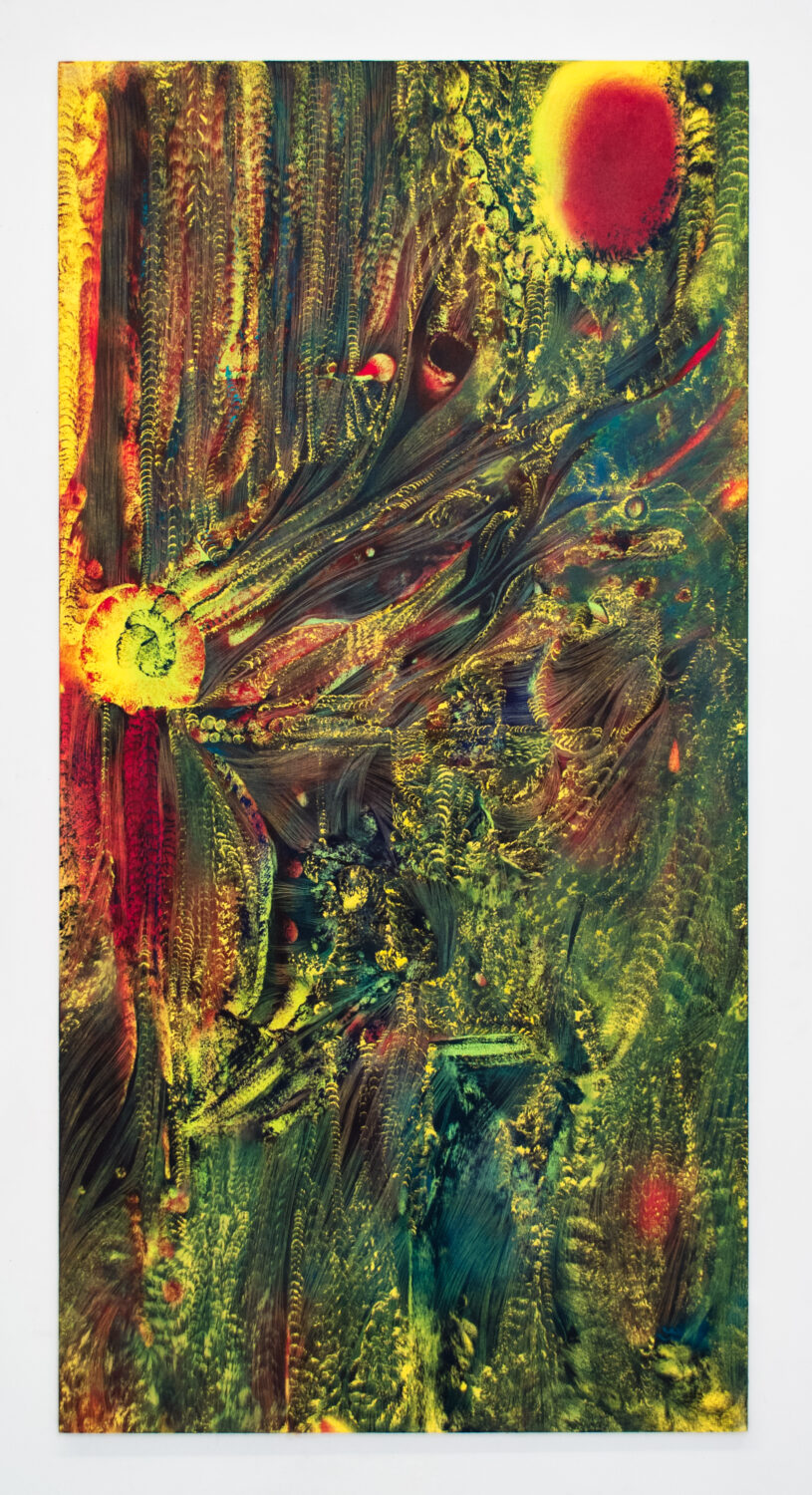

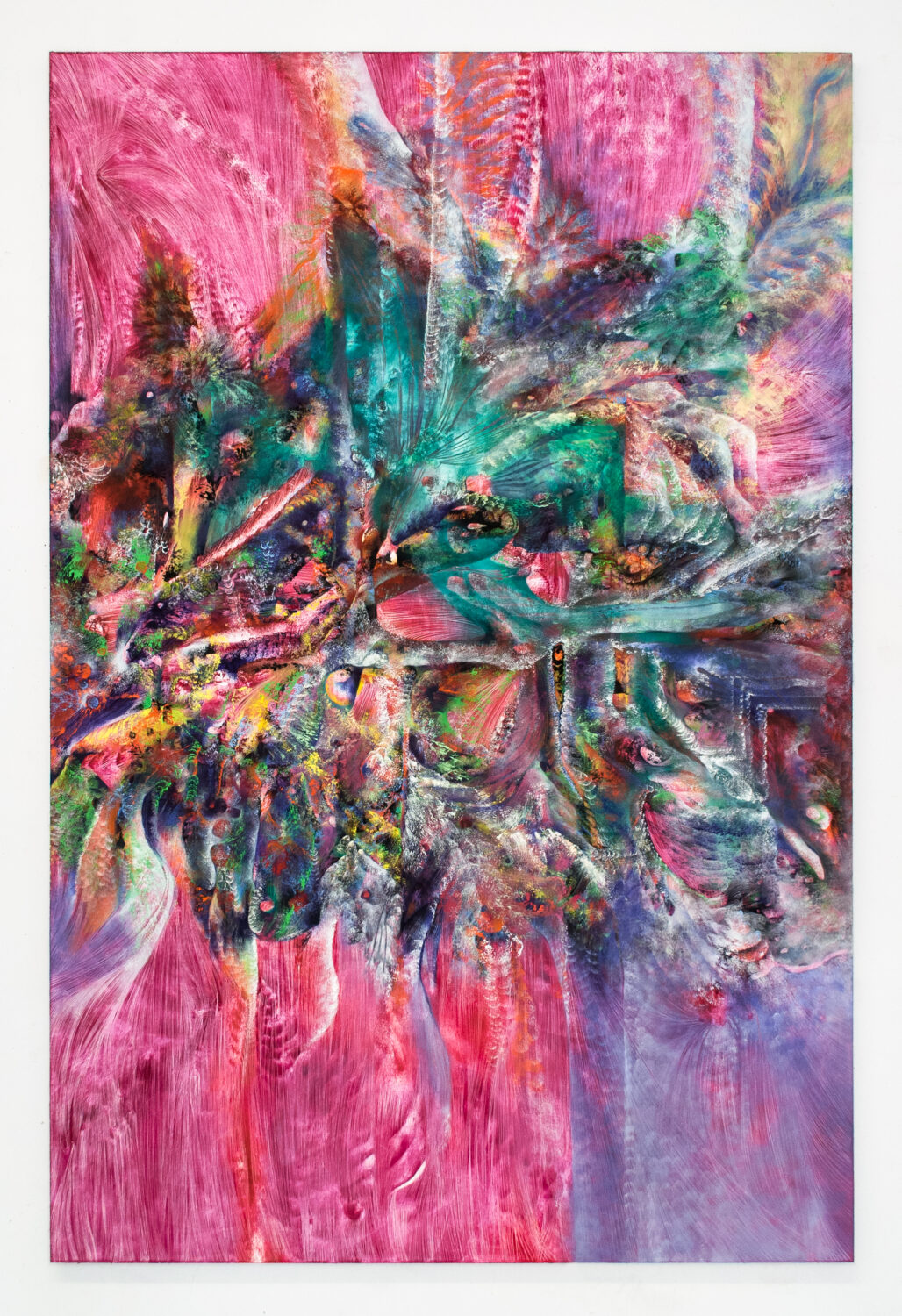

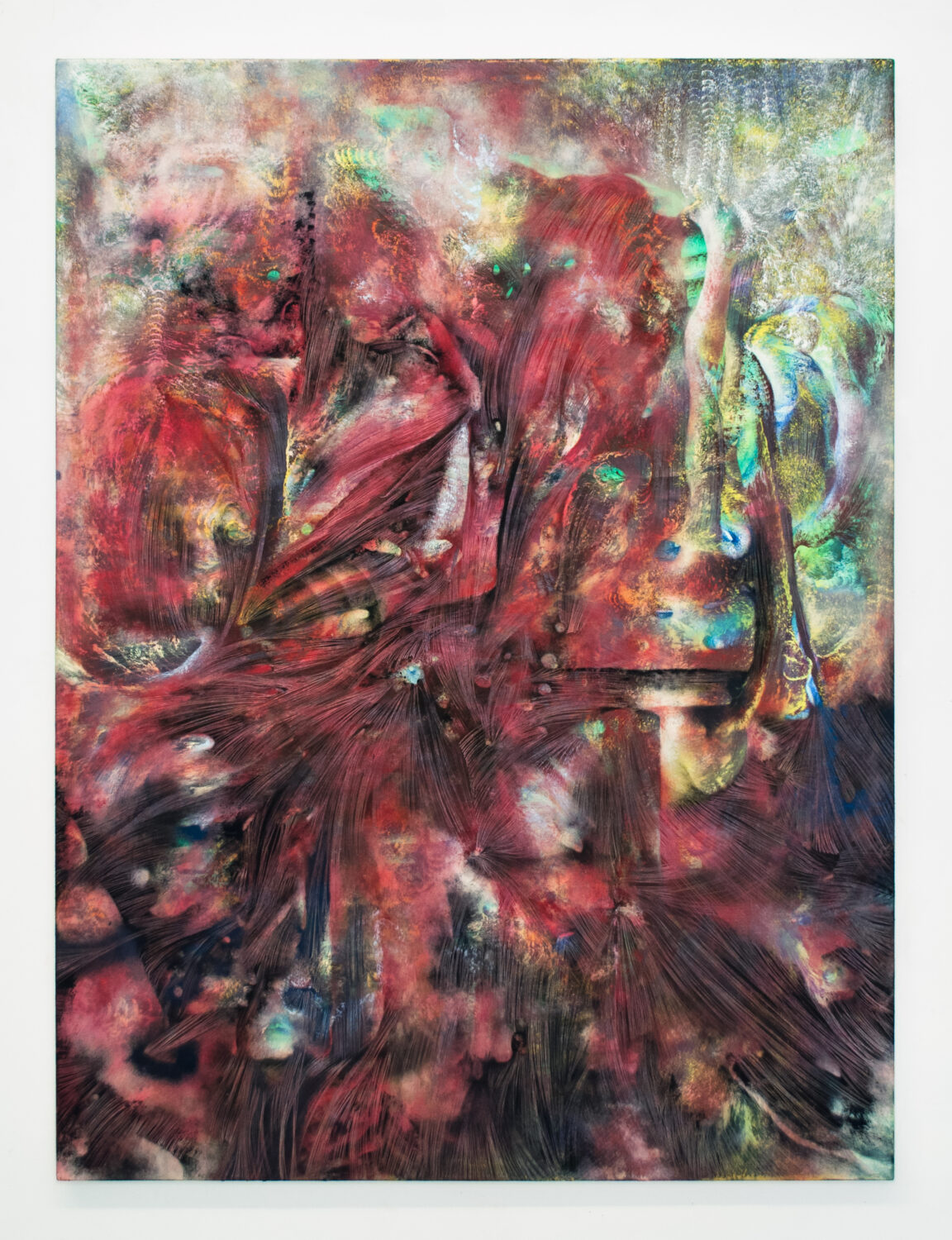

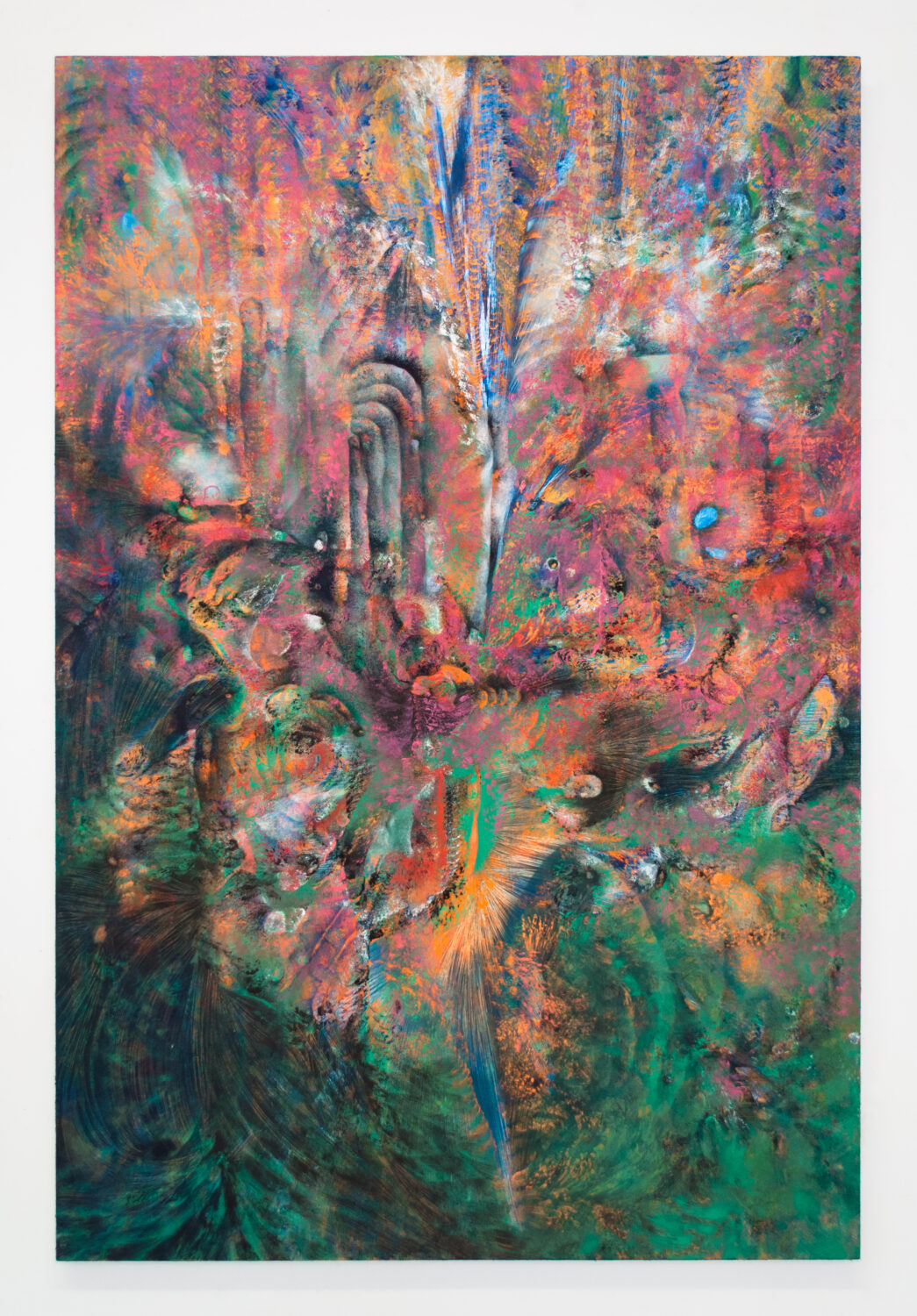

Lucy Bull’s lush, phantasmagorical paintings hail from just such a disquieting, uncharted waters. They appear abstract—blurs and arcs of acid color, skittering brush daubs, elegant, tendril-like scratches—but you’d have a hard time saying that they are strictly so. Certainly, they are not re- presentational in the traditional sense, either. Instead, they work slyly: they evoke, they allude, they duck and weave away from our knowing, like something just barely glimpsed as it darts past the corner of our eye. Look long enough at one of them and you might catch a glimpse of a Lovecraf- tian monster wriggling up from their depths, or find the painting twisting itself, Rorschach-style, into some fraught psychic tableau.

It’s no wonder that when Bull talks about making these works, she describes the process as so- mething akin to entering a fugue state. She tells me that for marathon stretches, often extending late into the night, she conjures her paintings into being by following hallucinatory shifts in their cryptic, inchoate content, adding brushstrokes as one might grasp at the hazy details of a half remembered dream after a fitful night of sleep. She sometimes refers to her paintings as “spirits”.

This quasi-incantatory process of creation beckons me to slot Bull’s paintings in next to the works of the Surrealists, rather than any peddlers of pure abstraction that I can call to mind. After all, you can find hints of Bull’s galactic dreamscapes nestled in the paintings of Max Ernst, and I have no doubt that if there were, in fact, creatures camouflaged in Bull’s thickets of paint, they would find a place among the totemic figures of Roberto Matta or Leonora Carrington’s demonic menagerie.

But, tellingly, the artist with whom Bull shares the greatest kinship is one who stands apart from the traditional cannon altogether: the multifaceted outsider Eugene Von Bruenchenhein. Von Bruenchenhein’s work wasn’t discovered until after his death, but he left behind a veritable trea- sure trove spanning a fantastic array of media and styles. His paintings, which were partially made with paintbrushes fashioned out of his wife’s hair, share an aesthetic and energetic signature with Bull, with their stuttering brushwork, electric colors, and evocations of mythical creatures and deep sea life.

I’d like to think that there is a reason behind this kinship that runs deeper than mere style, though. Like Bull, Von Bruenchenhein felt that in making his work, he was connected to something that transcended his individual mind, which he would channel into his art. In his lengthy speculations on the workings of the human brain which were found in his art-stuffed house, he described this process as akin to jacking directly into humanity’s ancestral mind. “One might desire to be a geneus (sic) and the many connections to the contained knowledge in the brain could show him how,” he wrote. “He would be one in a million, who could force the brain to give up the many secrets it had inherited from thousands of years. Once opened to this communication, the creative ability would be simple to him.”

Maybe Lovecraft was a hair too pessimistic. Indeed, while terrible entities might lurk in the deep pools of our unconscious, and dark secrets of nature may yet be hidden from our eyes, paintings like Von Bruenchenhein’s and Bull’s seems to at once encompass these dark possibilities, and push past them into a realm beyond. In their numinousness, they renew an ancient sense that art is not meant simply to be beautiful, but to stand as a modest testament to the great mystery of our existence itself.

– Chris Wiley