Past

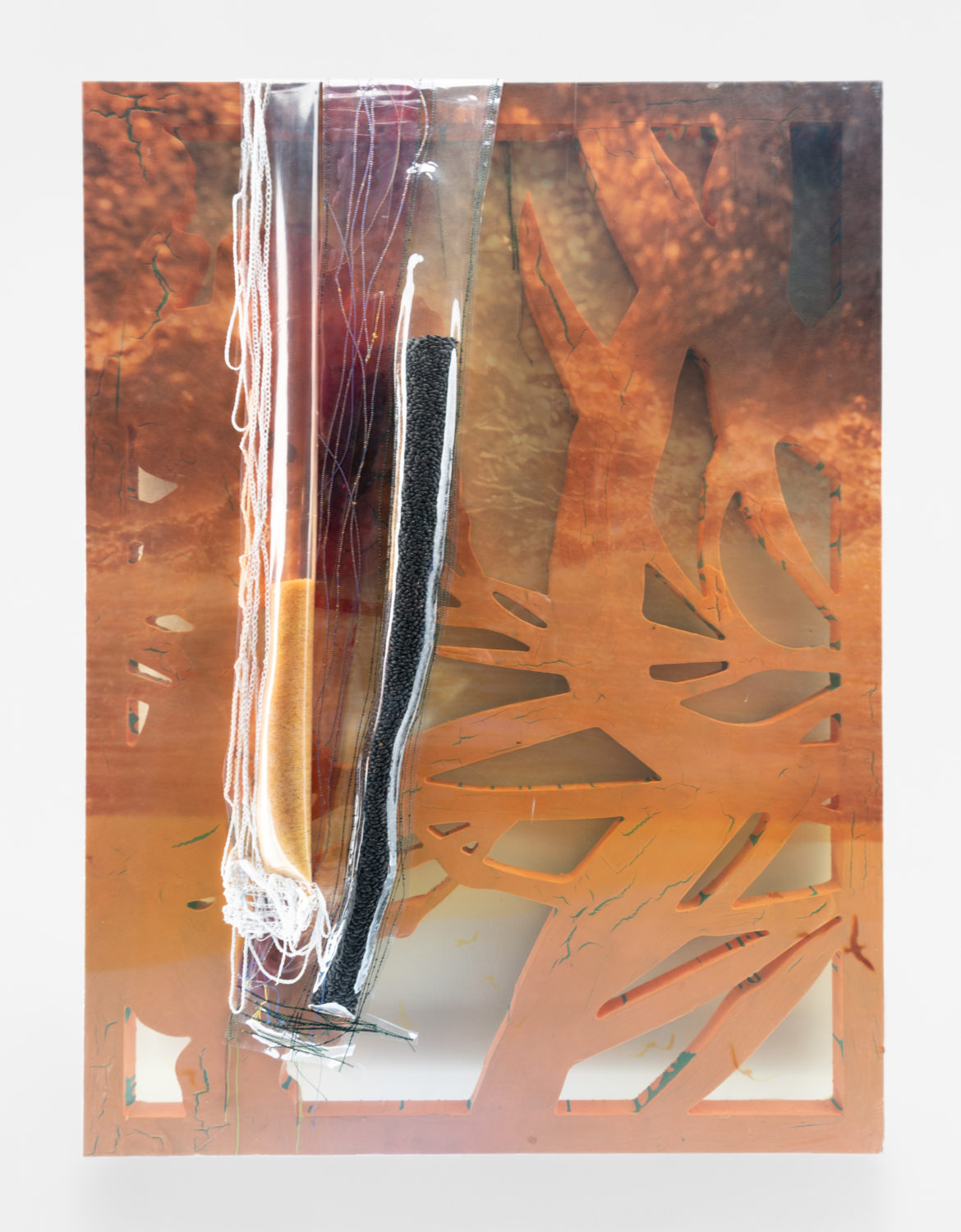

Julien Creuzet

The Possessed of Pigalle or the Tragedy of King Christophe

24 Feb - 06 May, 2023. Paris

Exhibition details:

Julien Creuzet

The Possessed of Pigalle or the Tragedy of King Christophe

Feb 24 – May 6, 2023

Gallery:

1, rue Fromentin

75009 Paris

The Possessed of Pigalle

In the center of Pigalle, two steps away from Moulin-Rouge, in a narrow dead end, a

discrete gate with a peephole bears a name as its only inscription: Mathilda Beauvoir. Not everyone can enter. “Who invited you?”, asks a suspicious voice through the door. This is neither a closed house nor a club for specialized tastes, but the only voodoo temple in Europe. Inside, about forty people, mostly white and very ‘sixteenth district’ are finishing an African-style meal (1), served by smiling black boys and girls. After the meal, two young drummers set up in front of their drums. It is 10:30 pm, and they will not stop until 4 in the morning.

Before the ceremony proper, a little par- ty takes place to warm up the room. Seven young Haitian women, barefoot and wea- ring blue dresses and scarves, start to sing and dance, hitching their skirts up around their waists while Mathilda Beauvoir, the ‘mambo’ (voodoo priestess), comes and greets the audience.

The guests are then invited or rather obliged to join the dance floor. Despite their obvious embarrassment, this very chic group have to dance to the rhythm of the drums, lie down onthefloor,playthe‘buttocksgame’,hold hands to form a circle, and all this under the critical and amused gaze of this group of young girls whose grace and suppleness are an embodied reproach to Western civilisation. The spectators are soon out of breath, and take a seat on small straw stools that are set out in a semi-circle. While the hosts prepare the ‘caye-mystères’ or the ‘bagui’ (the part of the temple housing the altar) and the officiants go to get dressed, Claude Planson, the former director the Théâtre des nations, author of the book Vaudou, un initié parle (2) and Mathilda’s husband, tells the story of the temple and explains the ceremony to come.

Eight years ago, a hundred or so French Voodoo enthusiasts joined forces to purchase this space in Pigalle and transform it into a temple. They also created an organization to promote the study of voodoo, which counts amongst its members renowned psychologists, sociologists and ethnologists. Its work has even attracted the attention of specialists at UNESCO, who have just designated Haiti as a ‘site of authentic culture’ as part of their campaign to safeguard ethnic groups.

A Voodoo community has gradually taken shape around the organization, composed of dozens of Africans and thirty or so White people. The ceremonies take place every week on Fridays and Saturdays. Except for initiation ceremonies, they are open to guests. The group of officiants rotates every ten months of so, since every year the community invites between twelve and fifteen Haitians to come to live in France, first in the Rambouillet Forest, where it owns another property, and later in Paris.

The women who we saw this evening are farmgirls from the countryside surrounding Jacmel. They carry out the same rituals here as they do at home: baptisms, marriages, initiation ceremonies, or, like this evening, sacred dances. How to define this religion–whose name brings to mind secret rites, black magic, and animal sacrifices, and whose followers have always faced persecution by Christian and pagan churches–other than diabolic?

“Voodoo is like a great universal spiritual current which, in the West, finds its expression in ‘mystery’ cults like those of Dionysos, Demeter or Mithra,” explains Claude Plan- son. “More precisely, it is linked to initiatory African religions of which it is a synthesis– although the Dahomey influence is particularly marked, the word ‘voodoo’ in fact originating from the fongbe term ‘vaudoun’, meaning ‘spirits’.”

“Voodoo is the cult of spirits of ‘loa’ who are at once natural forces and intermediaries between God and men. Though they are profoundly pantheistic, they believe in the single God, the ‘grand master’ that is the order of the world. It is he, they say, that ‘holds the stars together’; ‘his pencil has no eraser’, meaning even God himself cannot change what is written.”

“For the voodooists, beyond the visible world and the limits imposed by the poverty of our senses, there lies an invisible world populated by forces with which they seek to make contact. These forces can be favourable to us, and even immediately useful in everyday life, or they can be downright dangerous: everything depends on how they are treated. Hence the need for a ‘school’ (initiation) and for specialists (the ‘houngan’ and ‘mambo’, the priest and priestess).”

Malthilda enters, resplendent in a white lace dress with a large white headdress knotted into her hair. While the seven young Hai- tian women – the ‘hounssi’ or ‘wives of the gods’–also dressed in white outfits now, kneel before the large, drawn curtain and chant the preliminary songs, a young boy– one of the ‘hountogui’ or master drummers – traces out ‘vévé’ on the ground: symbols to represent the spirits they wish to invoke.

The ‘vévé’ are complex drawings made with cornflour, which is filtered between the index finger and thumb of the right hand with the regularity of an hourglass. Drawn from memory, there are hundreds of these symbols, some of which are highly intricate. The curtains open to reveal the altar and a diverse collection of ritual objects.

The ‘mambo’ welcomes and blesses the seven girls and the boy who drew the ‘veve’, who each come forward with a burning candle in their hands. And then, things explode: frenetic dancing, screaming, convulsions. Girls go into a trance, roll around on the ground, stumble into the spectators. They moan and are wracked by spasms, while others support them or tie scarves around their waists.

Mathilda herself, who at first simply watches her ‘followers’, calming them down and spraying rum in their faces now and then, is now in turn ‘possessed’ by a ‘hogou’, a war spirit. Tying a red scarf in her hair, she lights a huge cigar, chewing on the red end from time to time. She then grabs a machete and wields it this way and that, drawing some uneasy looks from the spectators. A large wooden bowl is brought to her, in which rum mixed with crushed leaves is set a flame; after dipping her hands in the burning mixture, she uses it to coat the dancers’ hands and arms with flames.

The initiate is ‘straddled’ by the spirit “Each ‘loa’ has its own specific character, which depends to a great extent on its functions”, explains Claude Planson. A ‘hogou’, a spirit of war and aggression, whose attributes are the red scarf, the cigar and the machete, will come on more strongly than ‘Erzuli Freda’, spirit of love.

“What should we make of the phenomenon of possession that is famously at the heart of voodoo? Over the last fifteen years or so,” Claude Planson tells us, “a vast amount of research has been undertaken in the West to discover the mechanisms of trance states, since we have come to understand that they can no longer be dismissed as hysteria or a simple ‘act’ somehow put on by entire peoples.”

“If we imagine phenomena of possession are the manifestation of impulses that originate in the ‘other scene’ described by Freud, the one which in reality determines our behaviour, Haitians are equally persuaded that they are provoked by forces that come from outside and which take possession of the initiate, ‘straddling’ them. Offering relief from the pressures of society, this ‘crisis of loa’ can be considered as a particularly effective form of psychotherapy.”

Without seeking to distinguish between the ‘theatrical’ and the ‘touristic’ elements in this show, which takes place every week at the Pigalle voodoo temple, we can only lament, along with Mr Amadou Mahtar M’Bow, Director-General of UNESCO (3), the ‘systematic disfigurement’ to which this popular religion has been subjected.

– Alain Woodrow (published in Le Monde on December 20, 1976)

(1) The meal costs 80 Francs

(2) Vaudou, un initié parle, by Claude Planson, 326 pages, Jean Dullis.

(3) See his preface to the book Vaudou, rituels et possessions, text by Claude Planson, images by Jean-François Vannier, Pierre Horay.