Past

Karla Kaplun

Carmen

14 Sep - 15 Oct, 2023. Paris

Exhibition details:

Karla Kaplun

Carmen

Sep 14 – Oct 15, 2023

Gallery:

1, rue Fromentin

75009 Paris

Image:

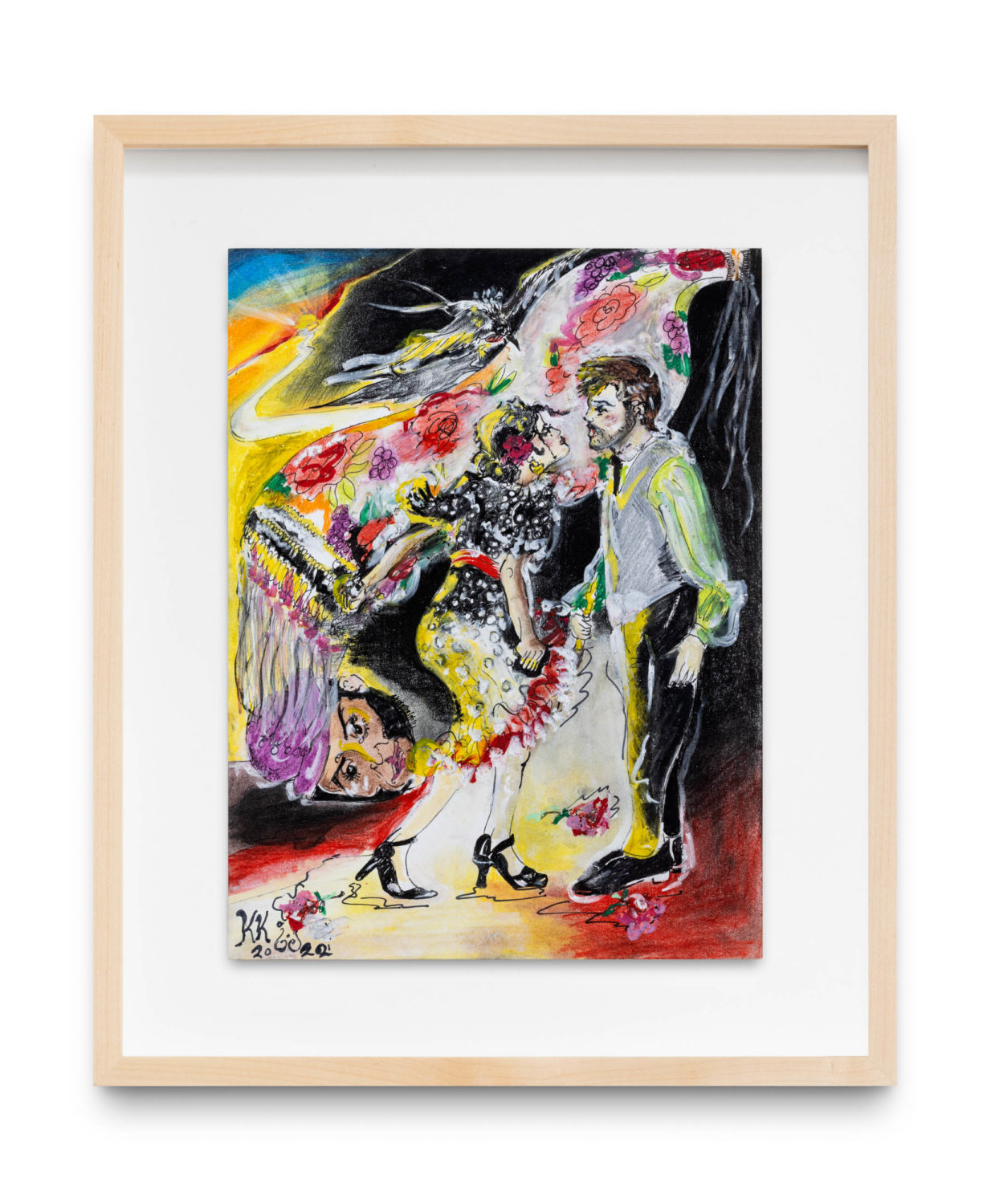

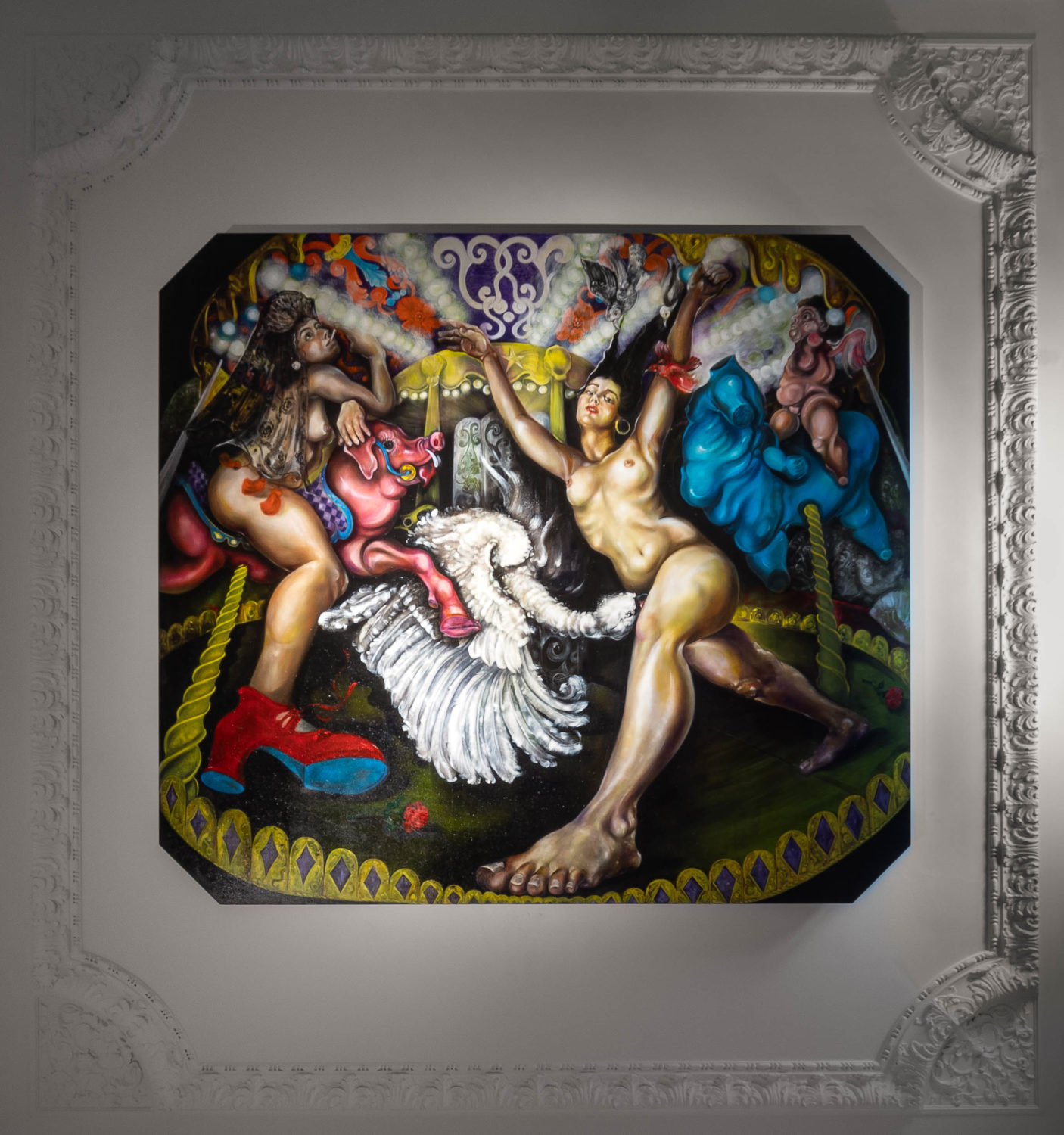

FINALE Tu ne m’aimes donc plus?, 2023

Oil on linen in carved wood frame

328 x 360 cm / 129 1/8 x 141 3/4 in

Written as a novel by Prosper Mérimée and later adapted for the opera by Georges Bizet, Carmen represents one of the first examples of European romanticism at the beginning of the 19th century and its ongoing fascination with Orientalizing Spain: those lands in the south of Europe that these artists described—without ever having set foot there—as unknown, savage and sensual, inhabited by the “other.” In his music, Bizet used tactics similar to those deployed by 19th-century writers and artists in their novels, travel diaries and paintings: through a pastiche of recycled images, he synthesized a confusion of identities—even those that might appear diametrically opposed—into a single consolidated truth.

The essentializing paradigms established in the opera still persist, reinforced in staging and picturesque dances, in Moorish sets and Manila shawls, and in Bizet’s musical arrangements, which used a wide range of motives vaguely codified as ‘Spanish,’ including Basque folk songs and ‘cubanas’ and even exotic melodies in vogue, in the composer’s day, in Parisian salons. That amalgamation of images and music that reinvented Spain from a ‘Western’ perspective is reflected, too, in the opera’s construction of character, particularly the juncture of gender, race and class encapsulated in the figure of the gypsy, specifically that of Bizet’s protagonist, Carmen. A criminal, a prostitute and a worker in a tobacco factory—site of the first feminine insurrection within France’s working class—Carmen represented virtually every possible category of otherness. Heavily invested by the libretto with ideas about the subaltern, Carmen stands as a threat to the ordered world, the institutions of family and Empire personified by Don José, the military officer from the Navarre whose fatal passion for the gypsy leads him to take her life.

The opera transforms Carmen into a public enemy who challenges the limits of decency imposed as much by the opera as by its audience, which saw her murder as a “symbolic masculine vengeance against the Arab World represented by a feminine figure; an exorcism of the morally alien.” Treating these subjectivities as antithetical exposes a deeper layer of meaning: The ‘norm’ can only exist in opposition to ‘difference.’Carmen is not a story about fate, announced from the beginning of the opera by chords that remind of death.

Carmen rejects the romantic plot: she is incorrigible, defying it in each act with ever greater force. Might we, then, reformulate the question ‘Why does Carmen die?’ as something, perhaps, more productive, even revelatory: ‘For what and for whom is Carmen killed?’The death of Carmen at the hands of Don Jose confirms the trope of the flesh tied equally to anachronistic ideas of sacrifice and to the Christian prohibition against erotic temptation. Flesh is the excess veiled by Christian ritual, that flouts the laws of decency as well as those of order and progress. The wafer of the eucharist, as much as the commitment to ideas of scientific progress, stand in clear tension with the concepts encapsulated by Carmen.

Erotic and barbarous,Carmen seduces and torments Reason and Decency with her libertine ideas; that same surfeit makes her, at once, attractive, demonic, Dionysian and free—but also unsettling. She stands in for the intuitive world of enchantment, passion, magic, the occult—of the subaltern as opposed to theRomantic ideal. If Carmen blasphemes against the Sacred and the Good, it is precisely because, from her ‘barbarian’ standpoint, the Bad does not exist. In the logic of the opera, impurity is condemned as profane and, therefore, the dangerous.“Will you come with me, demon?” Don José exclaims in the opera’s final act in a desperate final attempt to legitimize the gypsy who has resisted assimilation throughout the libretto.

The frustrating impossibility of possessing, occluding or conquering Carmen’s body, which radiates liberty, is only exacerbated by conferring her with the possibility of redemption. The answer thatDon José receives, which confirms his fears, is Carmen lived free and free will die! Her death is inevitable, then, not because of the irrational jealousy of romantic passion, but rather for a ‘greater good’: To save both Don José and Carmen herself from her otherness; to save the Empire from barbarity and the barbarian from her own barbarousness.The death of the bull celebrated with clamorous cries of “Victoire!” and “Bravo!” in the bullfight, drowns out Carmen’s cries of pain as her lover stabs her.

The crime occurs in the same spatial moment as the sacrifice of the animal. This fascinating temporal superposition clearly suggests a collective exorcism, represented in two distinct spaces but at the same time. The pagan festivity of the bullfight—a vestigial ceremony based in the stoning of the sacrificial goat—is both negated and validated by Don José’s transgression.

The sacrifice is, in essence, the ritual violation of the Catholic prohibition against violence; in Carmen’s murder, the lover destroys the beloved woman as much as the bullfighter does the animal.But the audience also participates in the eradication of a figure who, for the previous hours, has been an object of fear. When the curtain drops and the audience bursts into applause before the opera’s liturgic ecstasy, they’re celebrating together the spectacle of a double sacrifice: The timeless offering of the bull dominated by man (nature: domesticated) and the expiatory death of the female protagonist whose person brought together a plethora of alternative ways of being.For Don José, Carmen is open to that excess of animalistic violence that, in registers both sacred and profane, transforms her death into a bloody rite and guarantees the permanence of the myth that surrounds her: An affirmation of life, even in death.

– KK